Steve Servais

Designing and building with

environment in mind

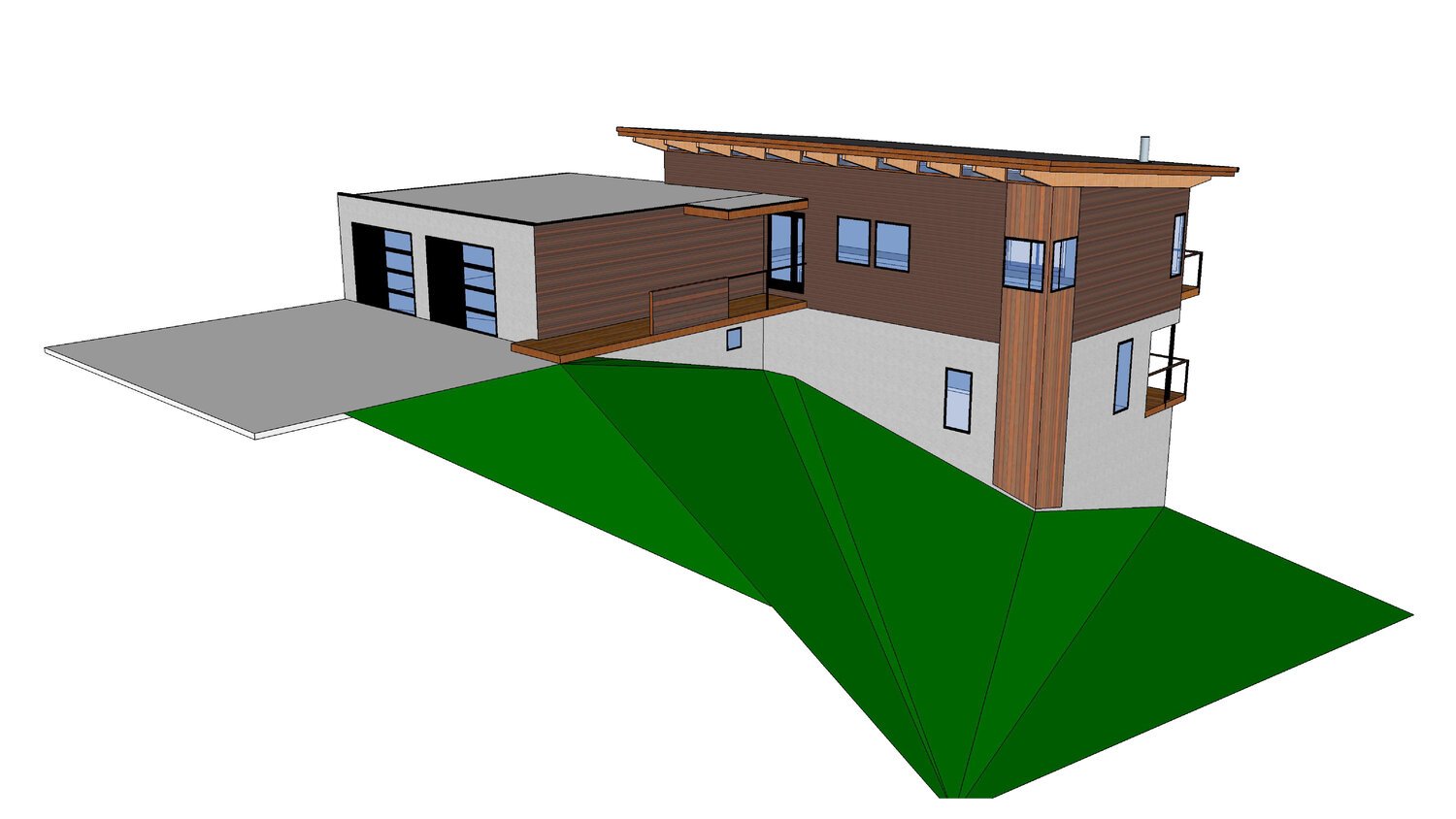

Meet Steve. Steve Servais designs and builds custom homes through his business, Common Advantage. He designs with the environment in mind, considering how a structure relates with energy inputs and outputs—especially free energy from Earth’s Sun. “I do a lot of my own design work,” he says. “I try to build about one custom house per year. But my philosophy with green building is that you definitely want to sail your house and not just hook it up to a more efficient outboard motor.”

As an example, Steve describes how the carbon footprint of a typical concrete foundation (making cement for concrete releases roughly 8% of planetary anthropogenic carbon dioxide) compares to the carbon offset from two years of output from a 5-kW rooftop solar array. So, while he is not opposed to solar photovoltaic, Steve takes a holistic view when considering the design and construction of “green” or “sustainable” homes, terms he considers imprecise. In addition to limiting the concrete used in home foundations—and deciding if a home needs a basement at all—Steve waxes almost poetic when talking BTUs (or, British Thermal Units, used to measure heat energy). It may not look as sexy as solar panels, but Steve is a big proponent of passive solar heating, where a structure’s siting and windows maximize their relationship to the Sun. “If you really want to be green, don’t build a new house at all,” he advises. “Buy an existing house and buy small. Turn your thermostat down and do all these other things [to manage energy inputs and outputs]. But if you’re going to build, I would say my favorite thing is correctly glazed windows that are facing the right direction, allowing for passive solar heat gain in our climate. You can achieve at least 60% of your own home’s heating needs—depending on insulation and thermal mass and other factors—just with the Sun.”

Steve followed a winding path to his vocation, each step an evolution in what he calls his “conservation ethic.” His father grew up on a wood-heated dairy farm in western Wisconsin. In the hills and valleys of the Driftless Area, Steve learned firsthand to appreciate the human connection to food, land, and water. “We had a huge garden and made most of our own food from that garden,” he recalls. “Canning and freezing and even hunting was a big part of our food source.” When he was 18, his father made Steve work as a masonry laborer, which led to lifelong experience with the construction industry. Steve loved working outside with his hands, but he also had an inquisitive mind to feed. At Marquette University he studied history, and seminars with Madison-based William Cronon introduced him to the field of environmental history. “With environmental history,” Steve says, “one of its key lessons is there’s an alternative to our built landscape. There’s an alternative to the way in which we’ve interacted with the Earth for decades or centuries or millennia. It gives you a different perspective on not only history but the built environment you see around you. Most people tend to just accept the world as it is, more or less. With the study of history… you can start to see how we got to now. And that, in fact, it doesn’t have to be this way.”

After college he joined the Peace Corps. Steve served tours in Ethiopia, where he met his future wife, and the Solomon Islands. Both experiences offered powerful contrasts in the way people lived and exposed the global extent of environmental damage. Steve entered grad school at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee to study environmental history, but he never stopped building houses, and ultimately he quit a life in academia to pursue his passion for green building and design. In 2005, he and his wife designed and built their own duplex in Milwaukee’s Riverwest neighborhood, which they sold in 2007. The economic downturn in 2008 made it difficult to build houses, and he now had a family to raise. For a time Steve worked in industrial waste management for WasteCap Resource Solutions and Kohl’s Corporation, which exposed him to large-scale systems with environmental impacts related to human consumption. But as the housing market recovered, he incorporated Common Advantage, LLC in 2013.

Over the past decade Steve has designed and built a number of custom homes in and beyond the Milwaukee area. Notable examples include the backlot “Machthaus” in Bay View built in 2015 for a client now almost entirely off the grid except for plumbing, and the former Riverwest home of prominent developer Juli Kaufmann. Steve also built Kaufmann’s current house, which was designed by Riverwest architect Patrick Jones and honored in 2017 by the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District as a Green Luminary® for incorporating green stormwater infrastructure. Steve has also built for architect Bruce Zahn, “who is probably the leading authority on passive solar design in Wisconsin.”

In addition to passive solar heating, Steve tries to use local or reclaimed materials in home designs, including hardwood flooring taken from older homes. He understands that his role in a niche market alone will not solve our climate crisis, but Steve hopes his designs can inspire people about practical choices we can make when it comes to how our homes relate to the environment. “People think that green building has to be more expensive. It really doesn’t. Not even one percent. It literally can just be achieved through better design.”

Steve’s firm, Common Advantage, built this Riverwest house designed by architect Patrick Jones.

In winter 2020-’21, Steve teamed with artist Sarah Gail Luther to explore the Harbor District as part of WaterMarks. He brought his environmental history and design perspectives to bear as a witness to what the pair termed the “heart of Milwaukee’s infrastructure.” “As someone who’s lived in Milwaukee nearly all of my life, I think of the Harbor District as more of an idea than a place—at least I did. It was invisible to me, both in my mental map of the city, but also it’s not a place that I would go, or I think a lot of people go…” Steve says. “But it’s a place that is undergoing a new revolution in terms of bringing people back, bringing institutions back. Such as Komatsu and also the School of Freshwater Sciences. A lot has come from conservation efforts with both the land and the water. I think having a cleaner environment is a huge part of that.”

Steve Servais in 2021. Behind his left shoulder hangs a hand-carved wooden mask from the Solomon Islands, where he served in the Peace Corps alongside his future wife.

Renderings of custom house designs built by Steve Servais’ Common Advantage.

Renderings of custom house designs built by Steve Servais’ Common Advantage.

Renderings of custom house designs built by Steve Servais’ Common Advantage.